Austin feels young, and so does its museum. The American collection at the Blanton Museum of Art does not cover the first 100 years of art of the nation, not to mention colonial times. Yet the presentation succeeds in holding an inviting angel that solicits comparison, connection, and communication.

In one room that features works of the Ashcan School, social realism, and regionalism, three pairs of human figures are hung together. On the left is Oil Field Girls by Jerry Bywaters, painted in 1940. In the middle is Thomas Hart Benton’s Romance painted between 1931 and 1932. From 1925 Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s Waitresses From the Sparhawk flanks the right side.

Both Bywaters and Kuniyoshi utilize a rather somber palette and both accentuate the human bodies with some degree of distortion that annotates their profession. Yet Bywaters has chosen to stay neutral by projecting the incongruity directly to the viewers while Kuniyoshi challenges viewers by mixing his own consciousness and commentary with the subjects. There is much openness in Bywaters’ setting. What is suggested is often contradicted by other elements – the bleak scenery of an oil field is jested with Coke and beer signs. The forlorn wheels accompany the invitation for dance and dining. The two females, slender and tall from the exaggeration and the low perspective, seem to ponder their own lives being surrounded by uncertainty. Kuniyoshi’s two females are enclosed in a tighter setting. Here the sexuality is subdued, if not denied, by the flattened figure form. Clumsy and stiff, they bear an intricate affinity to the sinister land. As pressing the backdrop landscape is, the raw power the two waitresses possess is greater still. If the coherent angularity between figures and landscape is not evident enough in Kuniyoshi’s painting, Benton’s Romance has interlocking patterns of sharp contours that bridge the slenderness of Bywaters and the clumsiness of Kuniyoshi. Hands clutched together, the black couple walks in a tilted plane as if they were gravitating into slow downward motion despite the tiredness. The lush green may soothe the bare feet, yet the house, tilted backward from the low angle, looks even more shabby and remote. Are they walking in a southern night dream? The spatial dislocation has a profound impact on the viewer and their perception of the title. If all three works could be accused of making caricatures of human figures, the fluidity in artistic expression and the tenderness and sympathy shown in the black couple make it the most intriguing of the three.

The only gallery that is dedicated to the art of the American West is snug between some 19th-century Greek and Roman plaster statues and European art galleries. Most came from the collection of C. R. Smith, an alumnus of UT Austin and CEO of American Airlines for many decades. Influenced by his fellow Texans Amon Carter and Sid Richardson, Smith began to collect Western art when he lived in a small apartment in New York City. The gallery keeps the cozy and intimate feeling with respect to the living space where these relatively small works used to hang. The nostalgia these works convey resonates with Smith’s own homesickness. Charles Russell’s Medicine Man was painted in 1916, eight years after he painted the same subject on a much larger canvas, now owned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. If the larger canvas strikes viewers with the artist’s faculty of bringing iconography and geology into his vision of man and spirituality, this small work speaks of poetry and endows a greater dignity and humanity to the central figure.

The main focal point of the room is a gigantic canvas The Charge by Frederic Remington, depicting an epic fight between the Calvary and American Indians. This painting came from Ima Hogg’s collection. Painted in 1906, three years before his death, the painting is a tour de force of Remington’s full embrace of impressionism in his signature subject. From afar, it does not look too much different from A Dash for the Timber, another masterpiece now hung at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, but the loose brush strokes make the chaos and menace even more pressing. How many New Yorkers had actually looked at the painting beyond the stereotyped western images in their own mind when it was hung at the Knickerbocker Bar Club of New York City? I am glad it resides in Texas now.

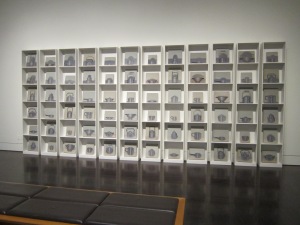

A contemporary work that takes a prominent space in the museum is La Vigilia by the Chilean artist Josefina Guilisasti. The work consists of a number of cubes where small paintings of aluminum pots, pans, and kettles in a variety of shapes sit. On the surface it simply puts common objects, often stored in a scattered manner in a cabinet, in an orderly and esteemed setting as if they were precious objects. The work is more complicated, however. It’s all about perspective.

These pots and pans it turns out are often used in government protests. The cacerolazo, or cacerola, meaning saucepan, gained notoriety in Chile in 1971 when thousands of women took to the streets of Santiago to protest shortages of basic household necessities. The empty pot is a symbol of the government’s failure. Signage at the exhibit identify the women who went into the streets as upper-class, perhaps drawing distinctions on the connotated meanings of the saucepans for members of different classes in Chile.

The monumental work is composed of 62 oil paintings and offers six different perspectives of the everyday pots. The work is a recent acquisition and a gift of the artist.

As a University art institute, Blanton Museum of Art may not be as comprehensive as other Texas museums, but it reflects a young and energetic city, that’s sure to make its mark on the art world.