A trip to Eugene has been on our TODO list for a long time. It was an exhibition from Karin Clarke Gallery that pushed us to take a day trip, but we were also rewarded with findings in Coburg, a small “antiquing” town just to the north.

Our first stop was downtown Eugene. The college town carries a familiar current of youth and energy, yet the downtown streets felt more mixed—different demographics moving at the same unhurried pace, drifting from the farmer’s market to storefronts or restaurants, as if time is slightly thicker here.

At Karin Clarke Gallery, “the Resale Show” demands a different level of effort and care than a typical solo-show. The coordination and logistics of assembling artwork from different patrons, collectors, and estates are challenging. That difficulty becomes part of the exhibition’s texture: each work arrives with the faint aura of a past home, a past wall, a past conversation. Most of the artworks are from mid-century Oregon artists who passed away in the last few decades. That fact alone changes the atmosphere. This is not just a display; it is a late chapter of circulation—objects returning to view after years of appreciation in private hands.

We came to the exhibition to learn, with a specific question in mind: Is there a style or a theme that could unite these artists and be coined as “Oregon School”?

That question has a trap inside it. The word “school” tempts you to look for a tidy signature—shared motifs, shared palettes, shared compositional habits—something stable enough to recognize at a glance. But a “school” can also be a looser thing: a network of teachers and peers, a geography that trains what and how to see, a set of shared conditions (light, weather, distance, materials) that quietly shape what feels worth painting.

As I had just finished Roger Hull’s monograph on Nelson Sangren (An Artist’s Life), I was happy to spot an important painting by the artist near the end of his life. Departure, or “Off to War Again,” as Sangren subtitled it on the back, is an ultimate collector piece. Although it is unclear what triggered the artist to paint a military draft scene, the painting has that rare combination of physical presence and compressed meaning: the energy from spatial planes joined through meandering architectures, the vibrancy from impasto built up by a palette knife, and the symbolism of a black bird hovering above. We did not take down the painting, but according to Hull’s book, Sangren wrote his message on the back – “58,000 killed in Vietnam for nothing! Were you consulted? Why not??”

If there is an identifiable school or Oregon art, a piece by Carl Hall titled “Dead Tree” fits right in. Despite the title, it nevertheless feels alive. Leafless and partially moss-covered, the tree looks both sculptural and amorphous. There is a quiet tension in the way multiple branches, well lit as if on a stage, stretch upward, echoing the towering firs in the dark background. Hall brought magic realism to a group of Oregon artists whose brushy style and strong colors were nothing alike, yet he expressed a shared experience of Oregon landscape: lush and fecund, yet permeated with dying—or, in Hall’s own word, “Eden”.

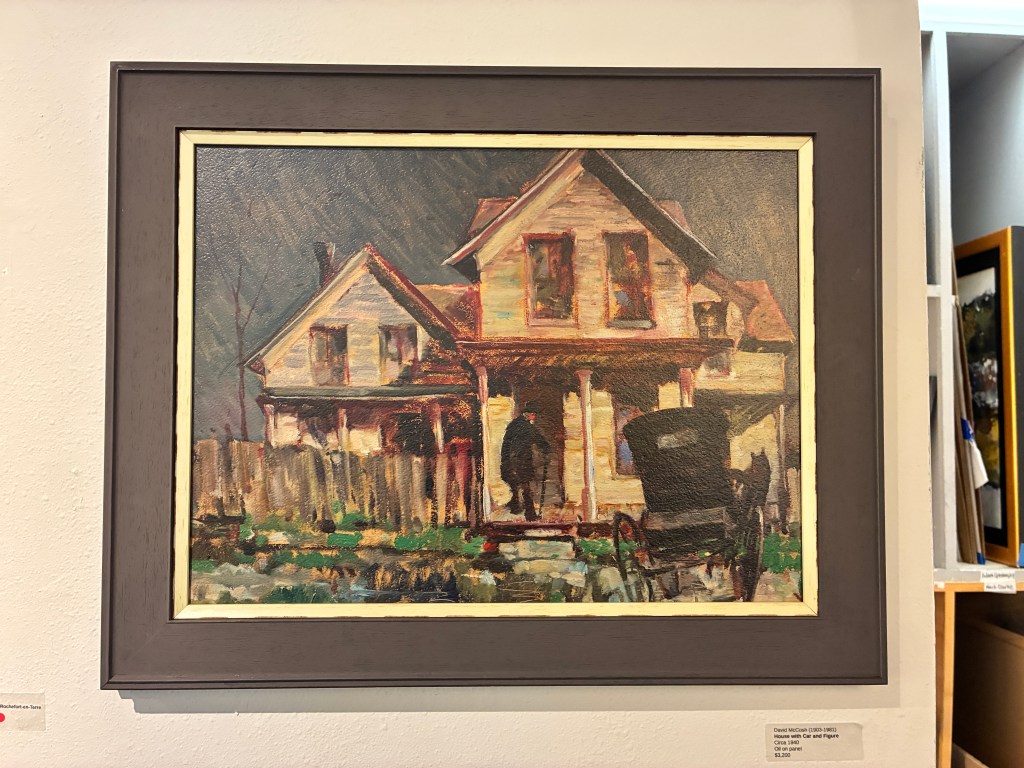

Also in the exhibition was an early painting by David McCosh from 1940, which still bears a regionalism mindset. Not far away, Tangled Growth from 1974 shows his signature style – vibrant colors and gestural lines that suggest a sense of direct observation and a spirit to capture the essence of the scene. Seeing the two works together telescopes time: one artist moving from describing a place, with tenderness, to translating the sensation of being there. The later work feels less like “a view” and more like a record of attention—how the eye moves, how the hand keeps pace, how a scene can become a set of decisions.

If there is an “Oregon School,” the exhibition didn’t convince me it is a single style. What it suggested, instead, is a shared seriousness about experience—about how a life in a particular landscape and a particular community becomes a set of artistic problems worth returning to. The closest I could come up with is that all artists create in response to their personal experience in both the natural and social world. Oregon’s dreamy and lush wild landscape becomes a recurring subject, but not in a postcard way. The land is not simply “beautiful”; it is formative, sometimes overpowering, sometimes intimate. It teaches scale and dampness and patience. To quote Ken Kesey, who lived most of his life in Springfield, near Eugene, “the hysterical crashing of the tributaries as they merge.. through tamarack and sugar pine, shittm bark and silver spruce- and the green and blue mosaic of Douglas fir.”

That quote matters here because it describes more than scenery—it describes intensity. If you bring that intensity back to the paintings, what stands out is not a shared “look,” but a shared willingness to treat the local world as something psychologically charged, not just visually pleasant.

The second art market show from mid-century artists also reflects a generational shift. In contemporary art, especially at a regional level, collectors tend to patron artists of their generation. Now, with the artists gone, collectors are downsizing and/or passing their treasure to the next generation. It is likely that the availability of the work in the market could see some increase in the near future. It remains to be seen whether younger collectors would continue to collect, exhibit, interpret, and research the art that they missed through first-person interaction.

That question feels especially sharp with mid-century Oregon artists, whose reputations often travel through local institutions, local memory, and the quiet authority of someone saying: I knew that painter. I bought this work directly. When that chain breaks, the work has to speak more publicly, more insistently, or risk becoming simply “regional” in the narrow sense—rather than regional as a source of distinct knowledge.

On the way back from Eugene, we took a short detour to arrive at Coburg. The town has five antique stores, almost all scattered along the main road within a three-block range. It’s the kind of place where occasional artwork waits for a second identity.

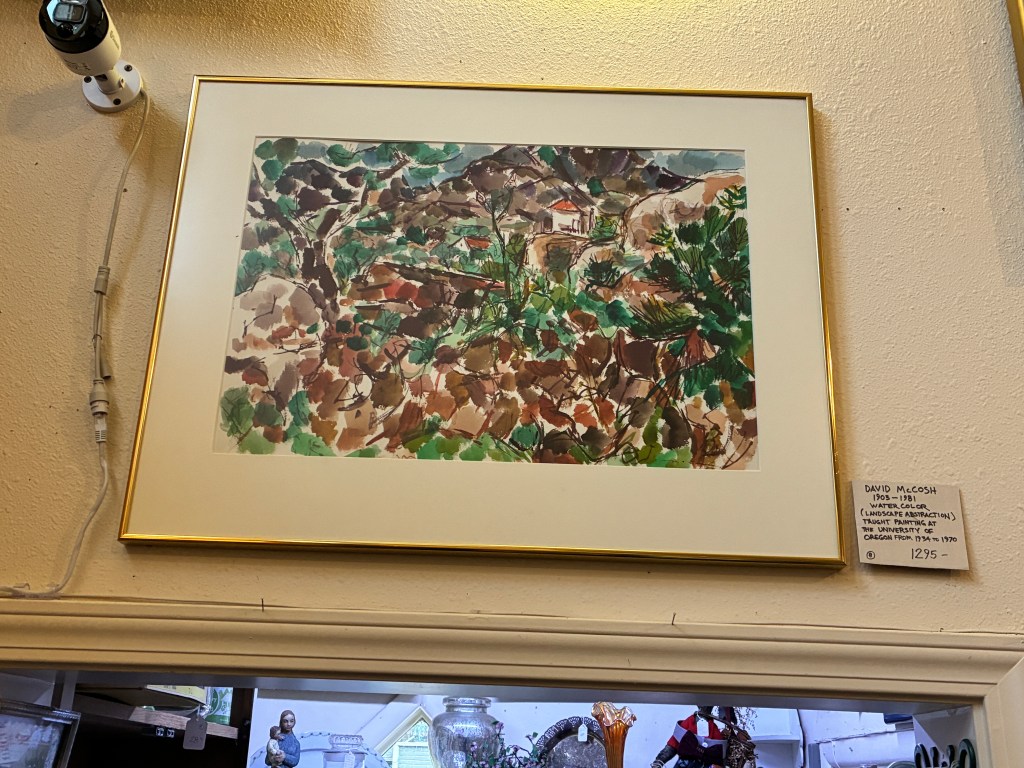

At Coburg Antiques Mall, I happened to see more artwork from Oregon artists. One watercolor painting by David McCosh (cover) is likely from the late 1950’s, during his sojourn in France. The distinct earthy, warm color palette can be found in his other watercolor paintings of that period. We brought home a litho print by Nelson Sandgren from 1982. Titled “At Bandon Beach,” (below) the artist created the print based on a watercolor painting with a similar composition. The litho, reduced to a monotonic grayscale, heightened the tension between dark rocks in the background and piled white logs in the foreground. Near the top of the print, Sangren used tushe to create a semi transparent cloud. The cloud softened the upper edge of the scene, while below it the forms stayed blunt and physical—rock, wood, weight.

Eugene educated us with an exhibition; Coburg rewarded us with a surprising find. I don’t pretend one day’s trip can define “Oregon School,” but it did loosen my original expectation. I arrived looking for a unified style; I left thinking the term may be less a conclusion than a set of ongoing relationships—between artists and landscape, modernism and locality, and the ways work moves between private keeping and public view.

Leave a comment