In the early 1800s, Philadelphia was a bustling center of science, printing, and trade — a city alive with the smell of ink, horses, and fresh plaster from its fast-growing streets. Among the booksellers, apothecaries, and merchants stood one man who would make a fortune not from medicine or publishing, but from blending the two. His name was William Swaim, and his product, Swaim’s Panacea, would become one of the most widely advertised and collected patent medicines of the 19th century.

William Swaim was born in 1781 and began his career as a bookbinder in Philadelphia. Somewhere around the 1810s, he shifted from binding books to bottling remedies. He started promoting a formula he claimed could cure everything from scrofula and syphilis to rheumatism and ulcers. By the 1820s, Swaim’s Panacea was being sold across the country — in newspapers, on broadside posters, and even through physicians who endorsed it.

According to early Philadelphia directories and advertisements, Swaim’s office stood near Chestnut and Seventh Streets, a prime location in the heart of the city’s commercial district. The neighborhood buzzed with printers, publishers, and medical suppliers — a perfect ecosystem for a patent medicine entrepreneur.

In Swaim’s day, Philadelphia was often described as the “Athens of America,” with thriving medical institutions like the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school and publishing houses that could print anything from textbooks to handbills overnight. The same infrastructure that spread new medical ideas also helped spread pseudoscience.

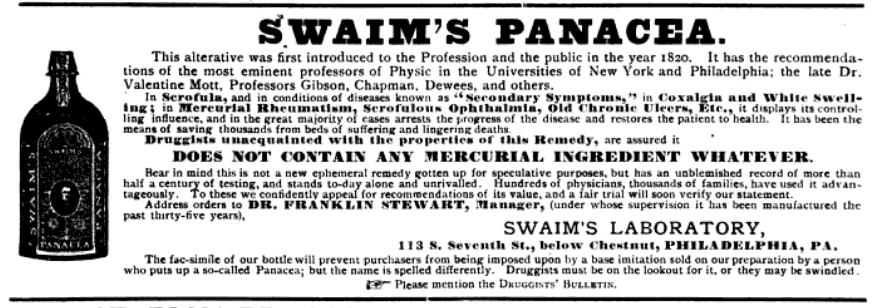

Swaim’s advertisements, some printed by the city’s top lithographers, were elegantly designed and filled with testimonials. They promised that his Panacea could “purify the blood” and “restore the constitution,” and his son later continued the family business under the name Swaim’s Laboratory well into the mid-19th century.

For years, the Panacea’s ingredients were a mystery. Competitors accused Swaim of using mercury chloride (corrosive sublimate) — a common but toxic remedy for venereal disease at the time. Modern historians and museum curators generally agree that the formula contained sarsaparilla, guaiacum, and mercury compounds, among other ingredients.

Doctors soon turned against it. By the late 1820s, Philadelphia’s medical societies were publicly warning against patent medicines like Swaim’s, which they considered dangerous and deceptive. Despite the backlash, the Panacea remained on the market for decades, long after Swaim’s death in 1846. Versions of it were still being sold around the turn of the 20th century — until the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 finally curbed its claims.

Collectors today prize Swaim’s Panacea bottles for their beauty and historic charm. The Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC) and several museums, including the Henry Ford Museum and the Smithsonian, hold excellent examples that serve as guides for identifying authentic specimens.

Here’s what to look for:

- Embossing: Most genuine bottles are embossed with “SWAIM’S / PANACEA / PHILADA.” (sometimes stacked vertically).

- Shape: Early bottles were rectangular or flattened oval, while later examples became round and ribbed, a style that’s especially eye-catching.

- Color: Expect to find bottles in aqua, emerald green, olive green, and occasionally smoky clear glass. The deep emerald ribbed types are particularly collectible.

- Finish: Authentic 19th-century examples have applied lips and visible tooling marks. Perfectly machined lips usually indicate later reproductions.

- Pontil marks: Most Swaim bottles were mold-blown rather than pontiled, but rough or irregular bases are a good sign of early glasswork.

Authenticity often comes down to detail. Compare the letter spacing and glass texture with known museum pieces or reputable auction listings. Tiny air bubbles and irregular glass thickness are typical of early 19th-century manufacturing and add character (and confidence) to a find.

Because Swaim’s Panacea was sold nationwide, examples turn up from New England to the Deep South, and even as far west as Missouri. Collectors most often find them at bottle shows, flea markets, and online auctions. Prices vary widely depending on color, embossing clarity, and condition. A bright, intact emerald-green ribbed bottle with sharp lettering can fetch several hundred dollars, while a common aqua example with chips may bring far less.

Bottles with complete labels or original boxes are extremely rare and highly prized. The labels, often decorated with engraved portraits of Swaim or ornate lettering, provide a vivid window into early American advertising art.

William Swaim occupies a curious place in American history: half healer, half huckster. His story mirrors the rise of the American patent medicine industry, a blend of entrepreneurial spirit, marketing genius, and medical guesswork.

Today, surviving bottles of Swaim’s Panacea are more than just collectible glass — they’re artifacts of a moment when science, commerce, and hope were all sold in the same container.

Sources and Further Reading

- Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC) Virtual Museum, Swaim’s Panacea entries.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Division of Medicine and Science collections.

- The Henry Ford Museum, catalog entry for Swaim’s Panacea bottle.

- Philadelphia city directories (1820s–1850s).

- The Medical Repository and other 19th-century medical journals referencing Swaim’s advertisements and controversies.

Cover: Digitally imagined rendering.

Leave a comment