In the autumn of 1920, Thomas Alva Edison—America’s most celebrated inventor—made a curious statement. During an interview with Scientific American, Edison mused:

“If our personality survives, it is strictly scientific to assume it retains memory and other attributes. If we could capture even one of those vibrations, we might—yes—record the voice of a soul.”

The remark, fleeting though it may have seemed, ignited a firestorm of public imagination. The press wasted no time. The headlines the next day shouted in bold:

“EDISON PLANS MACHINE TO TALK WITH THE DEAD!”

And yet, no such device ever materialized. No prototype was shown, no blueprints shared. Edison later walked back his comments, suggesting he had been speaking hypothetically. But the story didn’t end there.

The Sound of the Afterlife?

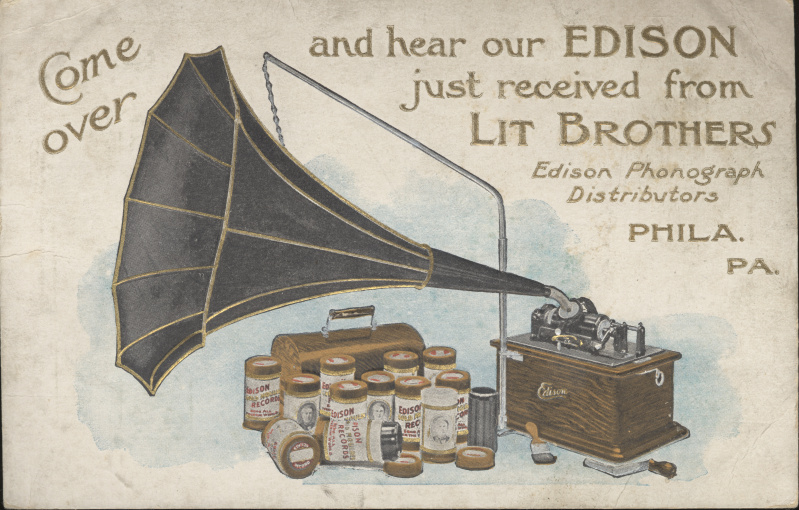

To understand the hold this idea had on the public, it’s important to consider Edison’s legacy. In 1877, he invented the phonograph, a machine that could record sound and play it back. The first words ever captured were his own voice reciting, “Mary had a little lamb.” For the first time in history, the human voice could be preserved—frozen in time.

What had once been ephemeral—a sound, a song, a laugh—was now permanent. The phonograph not only revolutionized communication, it altered the way people understood memory, time, and even death. Suddenly, a person’s voice could live on after they were gone.

Edison’s comment in 1920 built upon that very idea: if sound could be preserved, could the soul?

A Scientific Séance?

Edison was not alone in his interest in the unknown. Nikola Tesla, Guglielmo Marconi, and other prominent inventors had also speculated—some seriously, others less so—about the possibility of using radio waves or vibrations to detect “spiritual energy.”

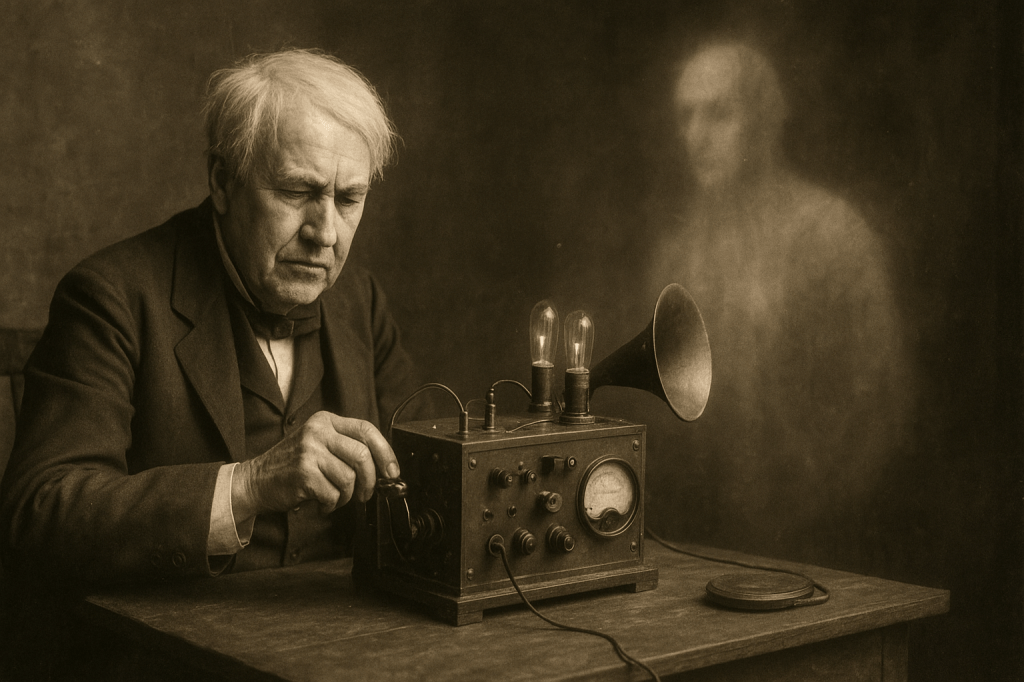

Yet Edison, ever the pragmatist, was careful in how he framed his ideas. He didn’t appeal to the supernatural. Instead, he suggested that if spirits existed, they might leave a measurable trace—perhaps an electrical impulse, perhaps a vibration too subtle for the human ear, but not for a sensitive device.

This was not mysticism; this was science, or at least the promise of it.

And therein lies the enduring fascination with what’s now called Edison’s Ghost Phone.

Fact, Fiction, or Forgotten?

Though Edison never unveiled a machine to speak with the dead, rumors have persisted for over a century.

In 1941—ten years after Edison’s death—Modern Mechanix published an article titled “Edison’s Ghost Machine,” claiming that the inventor had in fact worked on such a device, but had destroyed it before it could be made public.

No drawings, components, or physical evidence of the so-called ghost phone have ever been found. Still, that hasn’t stopped collectors, historians, and paranormal investigators from searching. Some believe the prototype was disassembled and hidden. Others think the records themselves—the wax cylinders—may contain fragments of forgotten experiments.

Edison’s Final Word

In his later years, Edison seemed to distance himself from the idea. But he never fully dismissed it either. In his diaries, he wrote:

“I have been at work for some time building an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this earth to communicate with us.”

It’s a tantalizing sentence—just vague enough to fuel speculation, just specific enough to suggest he may have truly tried.

Edison died in 1931, taking whatever truth there was with him. No machine was ever found. But neither was it definitively disproven.

The Legacy of a Whisper

Whether or not Edison ever succeeded in capturing the voice of a soul, he gave the world something just as powerful—the ability to listen back through time.

So perhaps, somewhere, in a dusty attic or mislabeled archive, an old phonograph cylinder still waits. A recording. A trace. A whisper.

A voice from beyond.

Leave a comment