Remember those bulky phone books that used to land on our porches with a satisfying thud? Most of us barely glanced at them before they went straight into the recycling bin. But here’s the funny thing—those books we once tossed aside are now collectible, sometimes selling for anywhere from $15 to $300.

And if you go back even further, before phones even existed, city directories were already doing the job of connecting people. The very first American city directory appeared in Philadelphia in 1785, thanks to Francis White. A year later New York followed, and by 1789 Boston had its own. By the 19th century, companies like R.L. Polk & Co. were pumping out massive annual or biennial editions. These weren’t just lists of names—they were packed with details: whether someone rented or owned, what their job was, even which businesses operated on your block. In other words, they were part census, part Yellow Pages, and part community snapshot.

That’s what makes them so fascinating today. For genealogists, they fill in gaps between census years, confirming where an ancestor lived and what they did for a living. For people curious about house histories, directories are gold. You can trace who lived in your home year by year—sometimes even learning their occupations, whether they were boarders, or if the property changed hands often.

I once picked up an old Portland directory at an antique store and, flipping through it, pointed out a listing for the shopkeeper’s grandfather, an Italian immigrant who worked as a mobile knife sharpener. Her eyes lit up. It was more than just a name—it was a snapshot of his life in a new country. That’s the kind of detail you won’t find in most modern databases.

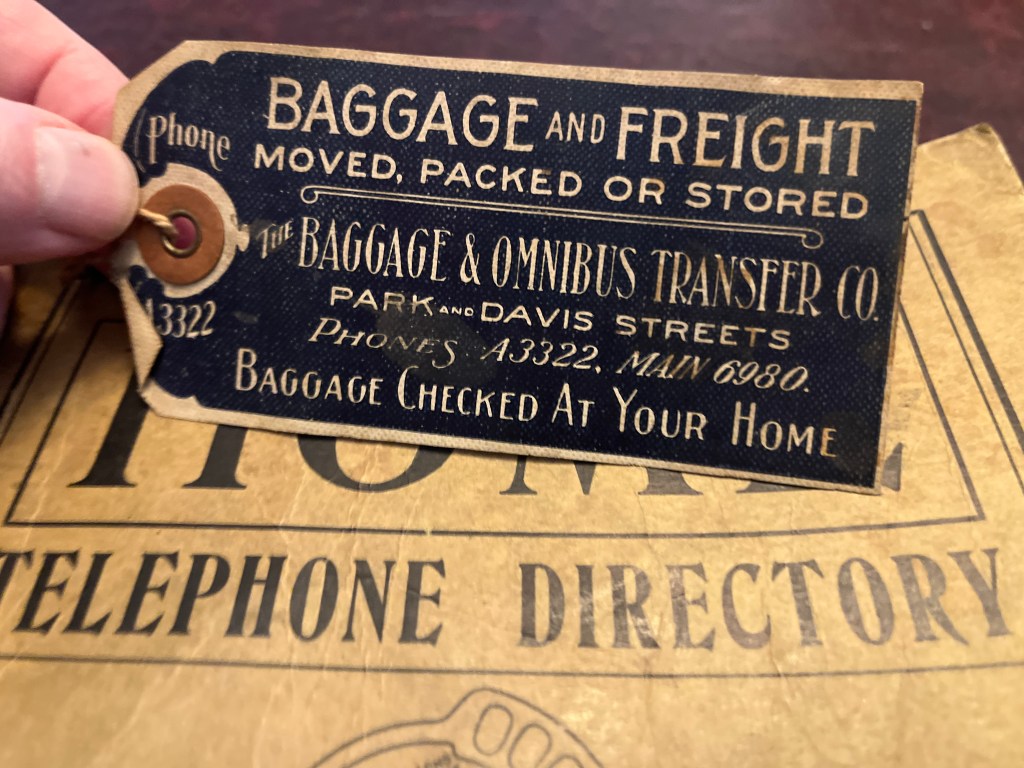

The rise of the telephone in the late 1800s added a new kind of directory. The very first “telephone book” appeared in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1878, and it wasn’t even a book—just a cardboard sheet with 50 names (no numbers, since the operator did all the work). By the 20th century, White Pages and Yellow Pages were household staples. For decades, they were the go-to resource for finding neighbors, local businesses, or that plumber who fixed your sink last year.

But fast-forward to the 2000s, and things changed quickly. Most U.S. households dropped landlines, phone books got thinner, and eventually disappeared. Today, the White Pages are virtually extinct, while the Yellow Pages limp along mostly as advertising pamphlets. We now rely on Google searches, social media, and scattered online databases to find information that once came neatly bound in one place.

And that’s part of the problem. The old directories were orderly, comprehensive, and reliable. Now, data is fragmented across dozens of websites, often inaccurate or outdated. Sure, digital tools like Ancestry.com and FamilySearch have scanned a lot of old directories, but flipping through the real thing still feels different. You can see whole neighborhoods at once, trace how streets filled up with businesses, or spot how occupations shifted over time.

So while we live in an age of instant access, something was lost when the big books disappeared. They weren’t just about finding a phone number—they were about capturing a community in a particular moment. For historians, genealogists, and anyone curious about the past life of their home, these directories remain an indispensable treasure.

Leave a comment