For a Portland transplant, how long does it take before the city feels like home? Locals might say it’s when you can correctly pronounce “Couch” or “Willamette.” For artist Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, it’s been nearly eight years. His first solo show in the city he’s called home since 2017—fittingly titled A Place I Call Home—at Russo Lee Gallery.

Quaicoe rose to prominence during the pandemic, a time when the Black Lives Matter movement reignited national awareness around racial injustice and inequality. While American discourse often flattens Black identity into a monolith of historic struggle, Quaicoe offers a distinct West African perspective. Rather than adopting a stance of defiance or subversion like Kehinde Wiley, Quaicoe channels an innate dignity—one informed by growing up in Ghana, where racial hierarchy is absent. His subjects exude quiet strength, grounded in self-possession rather than resistance.

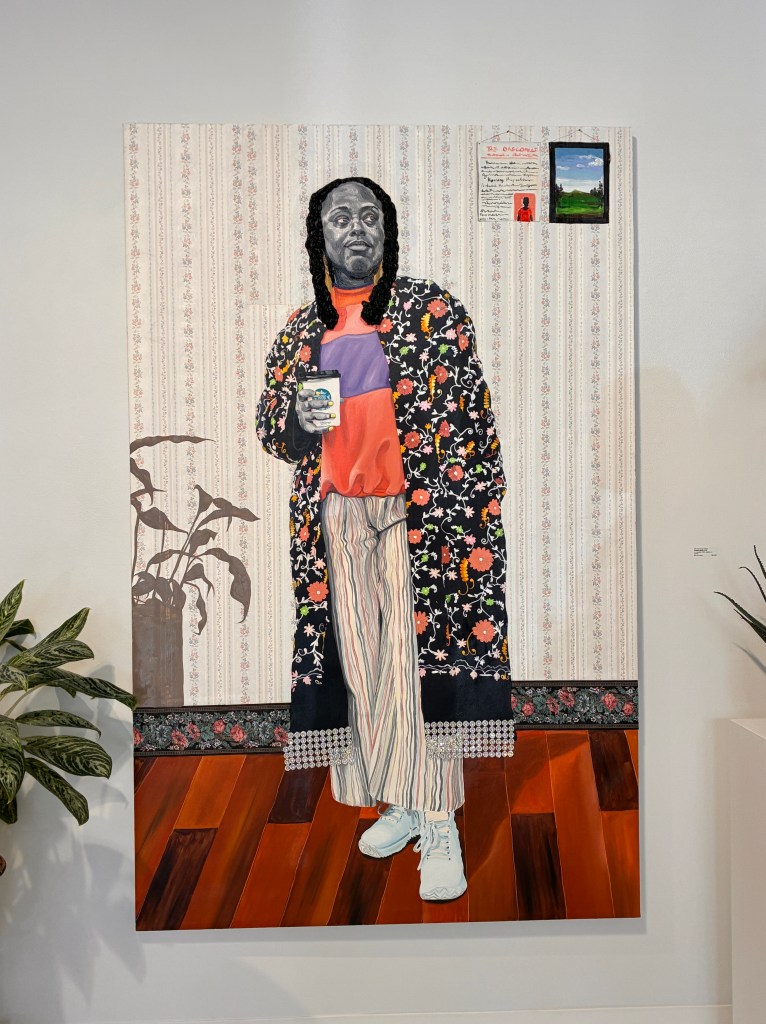

That radiating power pulses throughout the exhibition. In Intisar Abioto, his friend who first connected him with Portland’s broader art community, the subject leans slightly back, gazing upward and to the left. Her floral black robe carries as much presence as her gaze. Even as her thoughts seem elsewhere, her wide, confident eyes draw us in—they anchor her.

Portland, with its mellow climate and soft-spoken culture, tends to ease the anxieties of newcomers. Its people may be reserved, but they’re invariably warm, welcoming with a subtle touch. That spirit permeated the opening night. Many of Quaicoe’s sitters—some even dressed as they appear in their portraits—mingled with visitors in a scene that felt more like a neighborhood gathering than a formal reception. It wouldn’t have been out of place to hear Mister Rogers crooning “Won’t you be my neighbor?” in the background.

Alice, a ceramic artist and one of Quaicoe’s subjects, shared the story of their connection. “At an event, I told him I was a fan of his work,” she said. “Then he asked me to pose for a portrait. I couldn’t believe mine would be the first face you see when you walk into the gallery.”

Perhaps we owe this effect to Velázquez, who famously painted his assistant Juan de Pareja as a way of elevating his presence. Few marketing tools are as powerful as the sheer joy of sitters seeing themselves in paint. On opening night, Alice became a sensation, often found near her portrait, surrounded by visitors murmuring “wow” and “aha” in delighted recognition.

Quaicoe’s flair for theatricality shines in his attention to clothing. Like in opera, costume becomes character. Often rendered in bright colors against grayscale skin tones, garments serve as vehicles for personality and psychological nuance. Alice wore the same baggy pink sweater from her portrait—its chunky, white, knitted flowers barely hanging from her broad shoulders, layered over a worn black T-shirt. She even carried the same tote bag. “I didn’t even notice that detail until I saw the painting,” she said. “Fisk Gallery is closed now,” she added, fondly referencing the origin of the tote. Fortunately, the business will be remembered through this bag in her portrait.

Another portrait features young artist Xavier Kelley, who shares a studio building with Quaicoe. “It’s hard to find,” Kelley laughed. “There’s a Dutch Bros nearby, but if you’re not paying attention, you’ll cross the bridge over the Brooklyn rail yard, and miss it.”

Originally from Seattle, Kelley found kindred spirit in Portland’s creative community. In his portrait, he’s seen looking sideways, a paintbrush held in his mouth—as if caught mid-process, examining a work in progress. Kelley appreciated how Quaicoe included several of his own Afrofuturism paintings within the composition, as well as vintage toys displayed alongside the piece. “That’s my culture,” he said simply.

Other community figures featured include Dr. William and Nathalie Johnson, as well as John Goodwin from the Portland Art Museum. It was Goodwin who first arranged a studio visit that led gallery owner Martha Lee to represent Quaicoe. The Johnsons weren’t dressed exactly as in their portrait, but their bright smiles made them seem as if they’d just stepped off the canvas. Artist Garrick Arnold, observing the couple in the painting, remarked, “They look like the kind of people who, when they invite you over, you just know everything will be taken care of.”

During the artist talk, Quaicoe discussed his early influences and evolving practices: movie posters from his childhood, the dramas in black-and-white photography that inspired his grayscale palette, and the decision to use thick paint textures — especially during his Rubell residency, where he faced the largest canvas of his career. He also revealed a personal ritual: he always paints the eyes first. “I can’t go on until they’re done,” he said.

Then, a question came from the back of the room, with just two words — “Why Portland?”

It’s a fair question. Nestled in the Pacific Northwest, Portland lacks the glamour of L.A. and the media spotlight of New York. Yet with major acquisitions by top art institutions and three museums currently exhibiting his work, Quaicoe could live anywhere.

“Well, my wife is from here,” Quaicoe answered with a smile. “But why not Portland? After coming back from L.A.—after all that craziness—I thought, I like it here.” The Johnsons, standing nearby, nodded enthusiastically, nearly clapping.

Behind them stood a wall of quiet testimony: an artist becomes rooted when he finds his people and his community —family, friends, fans, and patrons—who come together to inspire, nourish, and sustain his creativity.

So, when does a transplant become a Portlander? Truman Capote may have said it best: “I live here by choice.”

Leave a comment