At the opening for his inaugural show with Guardino Gallery, recent California transplant Joel Briggs recounted an encounter about eight months ago with Donna Guardino, the late gallery owner. After an introduction by another gallery artist, Donna offered him a future exhibition on the spot: “How about a show next year?”

That moment may have sparked the creative ignition that culminated in a body of work quintessentially Oregonian. On a buzzing opening night, Gail Owen, who now carries the torch, observed the crowd from behind the front desk and remarked, “Donna would love to see all the red dots around on an opening night like this.”

Briggs renders the iconic landscapes of the Pacific Northwest with warmth and drama. Almost exclusively backlit, the scenes are bathed in golden light. “I just love the feeling when you look out and the sun is in front of you,” he says.

Our own experience of being blinded by the sun often evokes the scent of cool mountain air and the gentle awakening of skin stirred by light—moments charged with a primal sense of presence. Rather than avoiding the visual pitfalls of direct sunlight, Briggs embraces high contrast as a source of expressive power. His sunlit areas shimmer with vibrant color, while the darkest shadows pulse with rich, saturated hues. These shadows coil into serpentine forms that meander with both naivety and voracity, each edged by luminous silhouettes. In doing so, Briggs reveals not only the warmth and sensory allure of sunlight, but a deeper clarity and kinetic energy—illuminating what we might otherwise overlook.

His compositions are carefully devised by stitching together and transforming various photographic references. Often, He persistently examines the interplay between subjects, warping perspective until the final composition succumbs to align with his vision—one rooted in mood and storytelling.

Take In St. John’s Shadow, for example: shadow is how the work is meant to be read (as title) and seen. The two-point perspective exaggerates the scale of the bridge. The shadows willfully abandon the architectural details and extend as four parallel lines, arching forward, onto our feet.

The notion of romanticizing natural grandeur worked for the Hudson River School, at a time when few Americans had seen the untamed West or the exotic Andes of South America. But Portlandia’s collective intimacy with its surroundings might blunt such a “wow” effect—unless, of course, one sees it anew through transplanted eyes as is the case with Briggs who spent years in San Diego before moving to Portland.

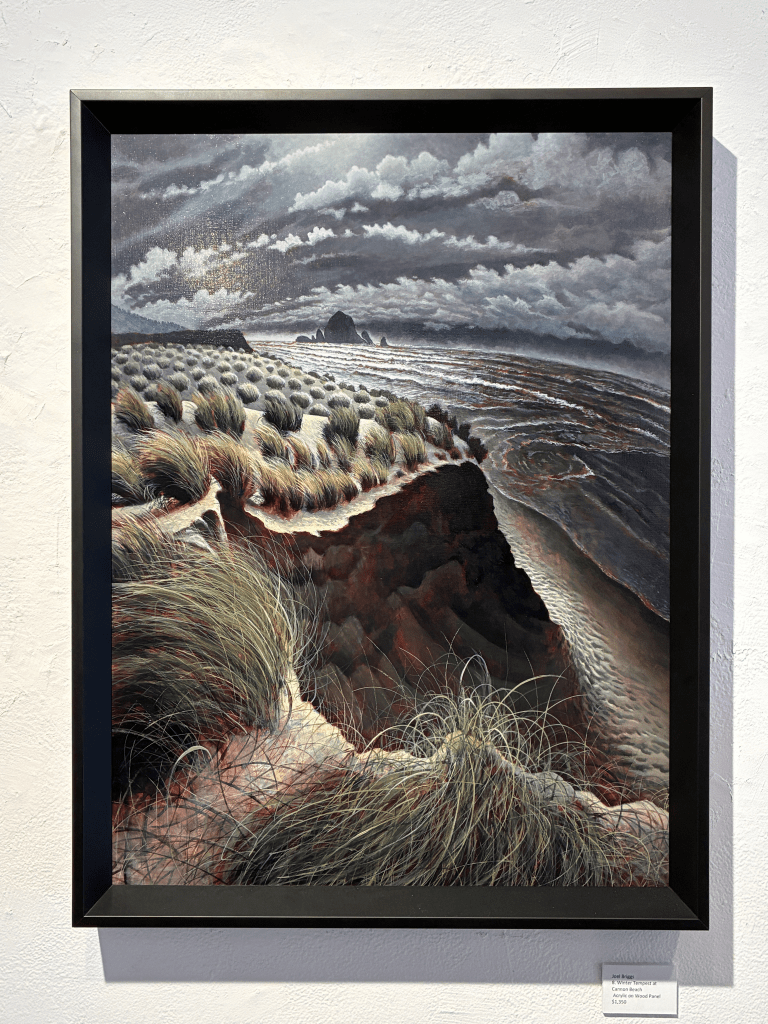

The unfamiliarity found within familiar subjects makes His Winter Tempest at Cannon Beach a standout. Even for locals, winter is typically a time to hunker down, with the seashore seen as a place to avoid—buffeted by torrential rain and chilling wind.

In this painting, nocturnal light renders the desolate beach bleak and eerie—yet it is anything but quiet. An army of tall grasses crowns a sandy cliff, blown sideways in unison, as if in defiance of the tormented sea, which hurls itself ashore in gusts of wind and white foam. The anthropomorphic quality of the grass strikes a chord in the human psyche.

That is the thrill from embracing the elements — experiencing nature as both beautiful and terrifying. In other words: majestic.

Wayne’s World

The crowds hadn’t yet made their way into the second room. Inside, Wayne Jiang stood quietly, lost in thought among his newly hung paintings.

It’s fitting that his work occupies the smaller room at Guardino Gallery—set apart from the dense crowd and low murmur of the main space. In his still lifes of restaurant interiors and floral arrangements, any human presence—whether within the painting or wandering the gallery—feels almost like an intrusion.

“You’re by yourself in here,” I quipped. “They’ll make their way soon enough,” Wayne replied.

Though congenial in conversation, Jiang can be remarkably precise. He gently corrected a visitor who described the interior scenes as feeling “lonely.” “Solitude, not lonliness. There’s a difference,” he replied.

Words matter—especially when they crystallize an artist’s intent. Loneliness suggests an unwanted condition, imposed by circumstance; solitude, by contrast, is a deliberate choice. It is in these quiet, contemplative moments—amid the most ordinary objects—that Jiang hopes we will discover scintillating visual pleasure.

As Eric joked, “Wayne must be doing well, considering how often he seems to eat out.” While I cannot confirm the truth of that statement, one thing is clear: these are not Michelin-starred establishments. They are intentionally nondescript, lacking any strong geographic markers—suggesting a kind of universal familiarity.

To his credit, Jiang meticulously records the source of each setting. For Chinese Restaurant Round Table, the reference is the Ambassador Restaurant and Lounge on Sandy. “The restaurant was okay. But the table setting was great,” he remarks while circling his thumb and index finger. Perhaps it is in these unremarkable restaurants where moments of solitude are more likely to arise.

However fleeting these moments may be, when captured in Jiang’s paintings they become visually resonant—rich in the vocabulary of geometric shapes, color, and line. Shapes intersect, interlock, and echo across reflective surfaces, forming quiet visual dialogues.

My personal favorite is Red Chairs Red Tables. It stopped me in my tracks as I followed how the corner of a red chair casts its shadow onto a slightly angled patch of light, framed by a nearby window. That patch of light then crawls upward over wood wainscoting, interspersed with parallel trim, then rising onto a soft blue wall. In that moment, every object seems to fall into perfect placement within an organic whole, as if guided by an invisible hand. Jiang is right: what could be more joyful than stumbling upon beauty in the most unexpected of places?

Beyond Guardino

If you’re heading to the Alberta neighborhood, it’s also worth visiting two nearby galleries. At Blind Insect, Birds and Biomes by Menka Desai features four sets of triptychs, each representing a distinct ecosystem: tropical rainforest, wetland, Sonoran desert, and the boreal forests of the far north.

At Antler Gallery, amidst hyperrealistic depictions of animals and birds, Yelena Bryksenkova’s small works on paper—created with gouache and colored pencil—introduce a quiet nuance and melancholy. Her uncanny visual language blends modern minimalism — often in flat and simplified forms — with an archaic register system that imposes a sense of structural hierarchy—all set within the familiarity of the domestic realm.

Leave a comment