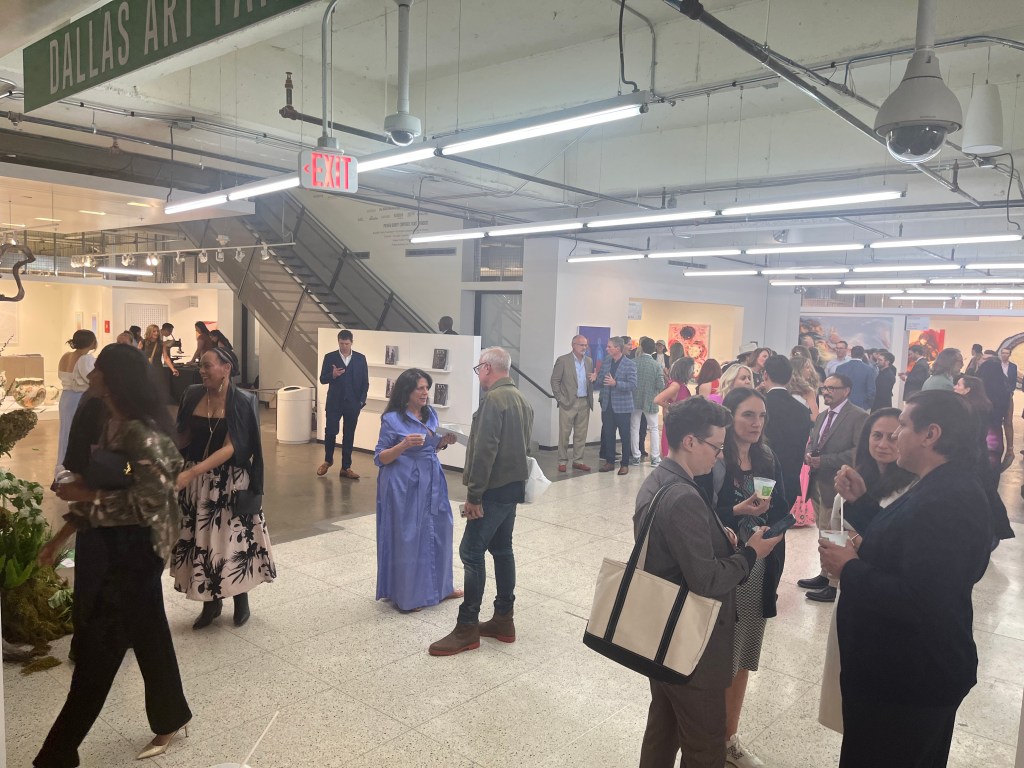

Can the contemporary art market offer a glimpse into the broader economy, or is it insulated from financial turmoil? We attended the 2025 Dallas Art Fair with these questions in mind. After a few years’ absence — during which we explored art fairs in Los Angeles and Seattle — we had the opportunity for a fresh look. Now in its 17th edition and with 91 galleries participating — more national and international than ever — this fair is solid.

Opening night started quietly, but soon buzzed with excitement as a crowd dressed to impress flowed into the venue. If economic gloom was looming, it certainly hadn’t dampened spirits at Valley House Gallery. We visited their booth first and many pieces were already marked with red dots, including a painting by Miles Cleveland Goodwin that felt both funny and sad at once — even a skeleton has to tread carefully to avoid his own demise. It was a moment of dark humor, strikingly pertinent in today’s political environment.

Art fairs often feel like Instagram brought to life: instead of endless scrolling, we stumble upon surprises and genuine delights — thankfully, without AI algorithms dictating what we see. Amid a sea of familiarity and strangeness, we sought to be smitten by an artwork in a heartbeat. Yet on an opening night, that’s a tall order amid hors d’oeuvres, cocktails, and chit-chat — when sometimes seeing feels less urgent than being seen.

Perhaps that’s why we were drawn to Matthew Craven’s work at Asya Geisberg Gallery (New York City). His geometric patterns, hand-drawn in ink on the backs of oversized vintage movie posters, appeared unassuming from afar; up close, the intricate details revealed themselves slowly. Some grids evoked mosaic tiles or American folk art, while others hinted at early computer graphics. There was no need to over-analyze the sources. The joy lay in the visceral pleasure of the mark-making itself — offering a brief but welcome refuge from the opening-night fanfare.

A similar quiet intensity radiated from Linn Meyers’ ink drawings, presented by Make Room Los Angeles. Gallerist Emelia Yin generously shared insights, flipping through a catalog of Meyers’ recent works and even pulling more pieces from a folder. Drawn on A4-sized vintage graphic paper, Meyers’ fluid, abstract compositions recalled the surreal precision of Dorothy Hood. Like Hood, Meyers creates a space filled with rhythmic tension — a metaphysical world where naivety collides with gravity, and subconscious shapes emerge unexpectedly. Several of Meyers’ pieces had already found new homes by the time we arrived.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with the desire to be seen. As Kevin Vogel of Valley House Gallery observed, half the Dallas art community seemed to be present that evening. We not only reconnected with artist friends like Celia Ebele and Eli Ruhala but also met, for the first time, Sophia Anthony — an artist who we hadn’t yet encountered in person despite owning her work.

The festive spirit was understandable. Artists had plenty to celebrate, as regional creativity was handsomely highlighted throughout the fair. Eli, still preparing for his MFA exhibition, was represented at Keijsers Koning Gallery. Most galleries focused on contemporary living artists, though a few made room for mid-century modernism — with women Abstract Expressionists exhibited by Jody Klotz, and Texas legends like Dorothy Hood at McClain Gallery and Forrest Bess at Franklin Parrasch Gallery.

Still, if there was one artist we wished we could have met, it would be Laura Footes, represented by Carl Freedman Gallery of Margate, UK. Meeting her would be difficult; the artist suffers from an autoimmune condition that profoundly shapes her work. In Quiet Night, Footes weaves a dreamlike cityscape with a fragmented interior scene: a lone, nude figure perched on the edge of a bed. Her permeable skin, rendered in succinct and fluid brushstrokes, suggested she was barely anchored in the world. The work’s dark bluish tones and theatrical tension compel viewers to stop, only to be caught in a suspended moment between reality and imagination.

How do we feel connected to someone so barely visible? Footes may experience alienation and loneliness more acutely than most — but we have all been there, especially during the pandemic. Despite living amid a jungle of skyscrapers and millions of souls, what all social platforms fail to offer — and what her painting seems to grasp — is that yearning to be known, truly known, by another human being. It’s a shared longing woven into the fabric of contemporary life..

Yet an art fair is, at its heart, a marketplace — and this creates a dynamic tension between gallerists and collectors. Most booths opted for a group show, casting a wide net in hopes of a sale. But for collectors considering a serious investment, the vending-machine approach sometimes falls short. A few galleries, however, courageously mounted solo shows. 193 Gallery dedicated its space to Ben Arpea, flooding a room with Mediterranean light and color. Ulterior Gallery (New York) and Tops Gallery (Memphis) shared a booth to co-present Mamie Tinkler’s mesmerizing series of candle paintings.

Tinkler’s sumptuous paintings defy easy categorization. Part still life (especially Vanitas art from the Dutch tradition), part photorealism, part surrealism, her melting, colorful candles might slip unnoticed into an Almodóvar film — yet on the gallery walls, they held a commanding presence. Mark Ducklo from Tops Gallery mentioned how Tinkler had learned to heat and bend the candles into whimsical shapes herself. When I asked about the vibrant colors, he shrugged and said, “Oh, you can find every color online.”

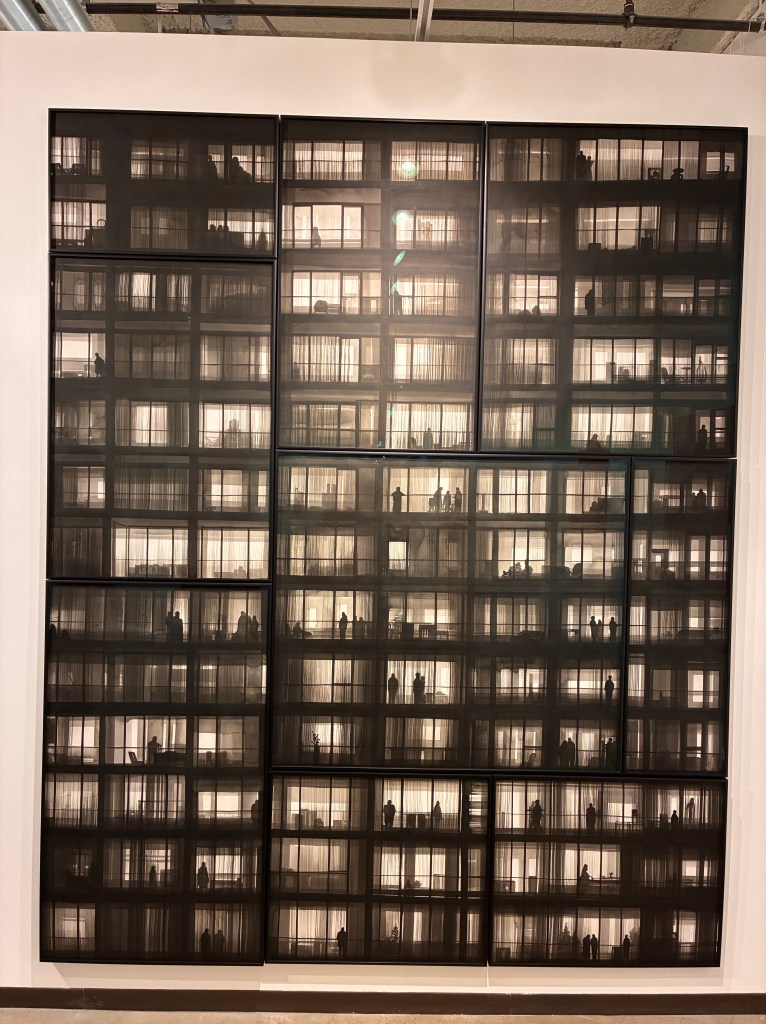

Part of the appeal of Tinkler’s work lies in its modest scale, making it accessible to collectors. After all, there are only so many large walls in private residences where works like Footes’ could be properly displayed. Similarly, the impressive ensemble of watercolor panels by Radenko Milak — depicting parallel solitude during the pandemic lockdown — would require a muted, expansive space with controlled natural lighting.

Scale and space also played a role in the allure of Darren Waterston’s landscape work, which stopped us at Inman Gallery. Small though they may appear, the mixed media paintings evoke an Oriental aesthetic, where great negative space activates a poetic, mystical pictorial world. Like Tinkler, Waterston reimagines a traditional genre — fusing Eastern spatial reticence and formal motifs (rising clouds, cascading rocks) with the symbolic language of the West.

As we continued wandering, unexpected moments of connection emerged — such as meeting two gallerists prominently featured in Bianca Bosker’s recent book, Get the Picture. Her portraits of the art world felt even more vivid now that we were meeting these figures ourselves. I admired Bosker’s spirit of immersive journalism, though I suspect she exaggerated or oversimplified aspects of the art world “machine” for broader accessibility. I chuckled when recalling her description of press releases as exercises in making the familiar unfamiliar — or the unfamiliar familiar.

Bosker’s praise for Erin O’Keefe had piqued my interest, and we were excited to see O’Keefe’s work in person at Dimin Gallery. Her non-objective photographs were painstakingly constructed with sculptural precision and painterly surfaces, and maneuvered through cast shadows and seemingly floating shapes. They offered an enduring ambiguity between visual perception and intellectual cognition — a slow-burn viewing experience that rewards the patient gaze.

Finally, we wandered into Jack Barrett’s booth, also mentioned in Bosker’s book. Barrett himself, while noting the economy’s uncertainty, seemed bemused by the surging crowds at the bar. It was there we encountered perhaps the most quintessentially Texan painting of the fair: Paul Rouphail’s Western Motel, featuring a deserted motel room and a meatball sandwich — unwrapped, barely eaten and haphazardly left on a quilted bedspread. Outside the window, barren hills stretched to a distant horizon, evoking the dusty landscapes of Alexander Hogue.

While it is easy to snub the notion of a Texas-themed painting by a Philadelphia artist represented by a New York gallery, I found it more poignant to see a rural subject inundated within a polished commercial space.

“There is more space where nobody is than where anybody is. That is what makes America what it is.”

Gertrude Stein’s America, as relevant today as it was a century ago, is celebrated at an art fair by wealthy patrons, with a thrill of voyeurism.

In the end, while questions about the economy lingered, the Dallas Art Fair — like the art itself — defied easy conclusions. Art may not predict financial futures, but gatherings like this remind us what remains worth investing in: connection, creativity, and the ineffable joy of being surprised by beauty.

Leave a comment