George Johanson passed away in October 2022, at the age of 94, right after we moved to Portland. Although we never met, the current exhibition at Augen Gallery pushed me to research the late artist’s portfolio and creative process. If the show has captured the essence of the artist, he was a curious intellectual whose art blends his life experience in Portland with quirky, dramatic, larger-than-life imagination.

“The Way of Water” draws on paintings and works on paper through a four-decade relationship between the artist and Augen Gallery. The water seems ubiquitous, as Portland is famous for its rivers, nearby beaches, and of course rain.

I did not notice the title until I checked the exhibition online. The thematic connection is not necessary as Johanson’s works are imprinted with his distinct style so that his works are easily recognizable – bright colors, bold forms, inventive angles, hectic happenings, and a sense of space through dark and light. On the opening night, the exhibition blew my mind and left me with little capacity for other shows. A few minutes in another gallery and I felt a pull back to Augen.

It is hard to deconstruct the recipe for Johanson’s unequivocal style. Largely narrative with figural components and strong colors traced back to abstract expressionism, his works defy simple categorization. Instead, we’re continually presented with surprises like multiple perspectives, symbols, and elements of surrealism. Nevertheless, there are repeating motifs throughout the show that define who he was as an artist.

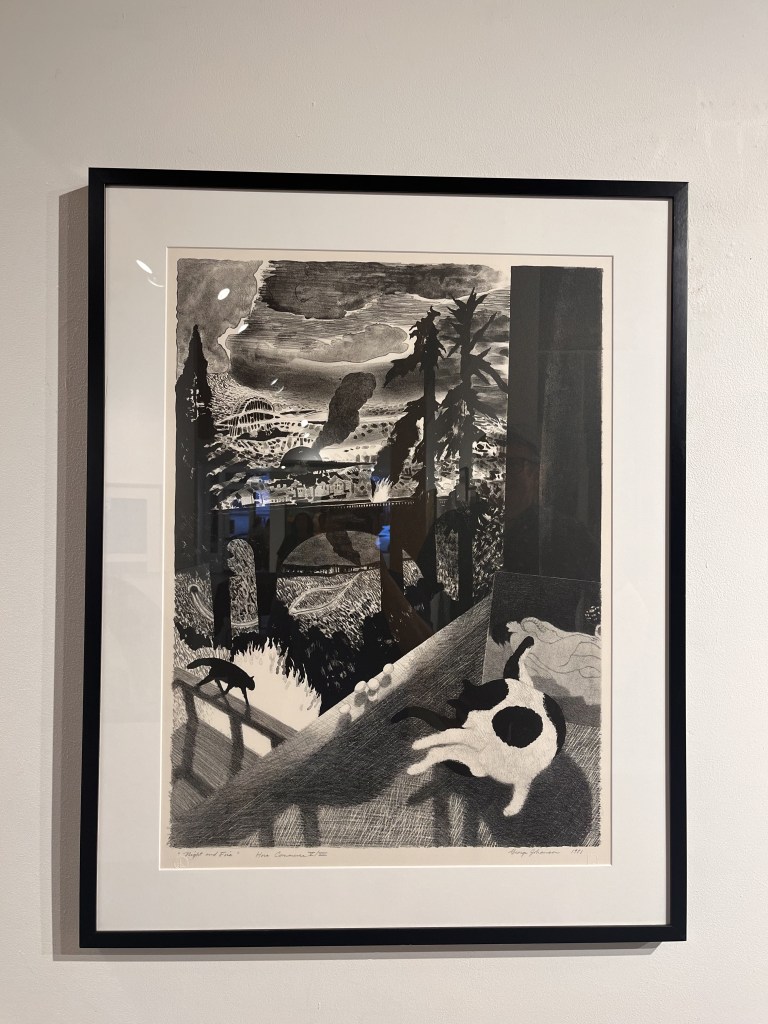

Bridges are one of them. Johanson lived right by the Vista Bridge in Southwest Portland. The high arches create unique openings for sectionized city views. The artist would further accentuate the height of the arches and show the bridge in many pieces. In Night and Fire, the bridge, in its complete shadow, enables two skies to be depicted within one image. Here, the night is full of commotion. Besides a volcanic eruption, possibly a reference to Mt. St. Helens, which exploded in 1980, he added a car fire, a building fire, and a possible forest fire, all within one view.

Those familiar landmarks are undeniably Portland, yet they were tossed in with artistic liberty. Like the elusive story that Johanson was about to tell, such re-arranged landmarks beg viewers to let their guard down and use imagination instead of memory (it doesn’t really matter which mountain it is or when) to fill the unsaid legend in his narrative. As if to provide an editorial comment, a nonchalant black and white cat is licking her butt, against Corbertt’s painting The Sleepers. In one of his virtual talks with the Arlene Schnitzer Museum of Art, Johanson mentioned that he loved to find thrill through double meaning. Here, I suspect he may say: “Well if sleepers are aroused, who else could fall asleep?”

That lithograph on paper was commissioned by Augen Gallery in 1981 and is probably one of the earliest works in the exhibition. In contrast, Untitled 2 was painted just last year. Throughout his career, Johanson came back again and again for a series of “waiting for the parade.” In his own words, he treated the subject like a still life where the curb forms a horizontal line near the bottom just like a tabletop, on which a crowd with different gestures resemble arranged objects in various sizes, shapes, and light. More often than not, he suggested rain with either streaks of puddles, reflections, or umbrellas. In this painting which is likely to be the last in the series, the umbrellas create rhythmic focus points, like stanzas in a poem.

It is also in this painting that I started to appreciate his color choices. Johanson seemed to favor bright colors that are more tuned to emotion than representation. In this near-monotonic painting in red (cover), except for a few spots of cool blue, forms were created through variation in shades and vibrancy. Unexpectedly, each umbrella completely changes the shape of the figure beneath as both assume similar tones, thus melting into one. Compared to the surrounding lanky figures, people with umbrellas look almost flowery. In doing so, Johanson elevated a mundane moment to something exciting.

Another distinct artistic vocabulary in his faculty is the composition style. In Split City 2, a vertical line divides the canvas into two parts, slicing the Marquam Bridge into misaligned sections. It poses the question upfront: What’s going on here? And like any great narrative painting, it asks questions instead of providing answers and captured my attention right away. Essentially, the off-tilt perspectives invite viewers to discover the process of reconciliation. Similarly, in Early Morning Row, the yellow-orange light of a boat storage’s interior frames the blue water and the sky within. Aesthetically, it bears more resemblance to Joseph Albers. The wide-angle view squeezes stacked boats into concentric lines. In the center, the distance to the Fremont Bridge and the vista beyond seems to be shortened through a zoom lens. Johanson was a lifelong paddler. It occurred to me that in one painting, he showed us the action he was about to take and the enchanting view that made him get up in the wee hours of summer days.

Regardless of the complexity of the composition, there is a sense of space within those images. For sure, a wide angle helps. In Carrying the Boat, the figure at the far end is so small that it makes me wonder if that boat is super long. Yet the artist also supplied spatial relationships with contrasting shapes between light and shade. In Night and Fire, a cat is shown in silhouette against a backdrop of fire, which in turn glows against a canopy of dark trees. Later in his career when Johanson decided to try reduction linocut like the rain series shown in the exhibition, he resorted again to the interlocking shapes of light and dark for spatial subtlety. The process and material were new and necessitated more angular forms and line drawing, but dark figures, no different from those carrying boats or bathing on the beach who are locked in their own momentous gestures, ground the pictorial space that would be otherwise floating in the airy lightness.

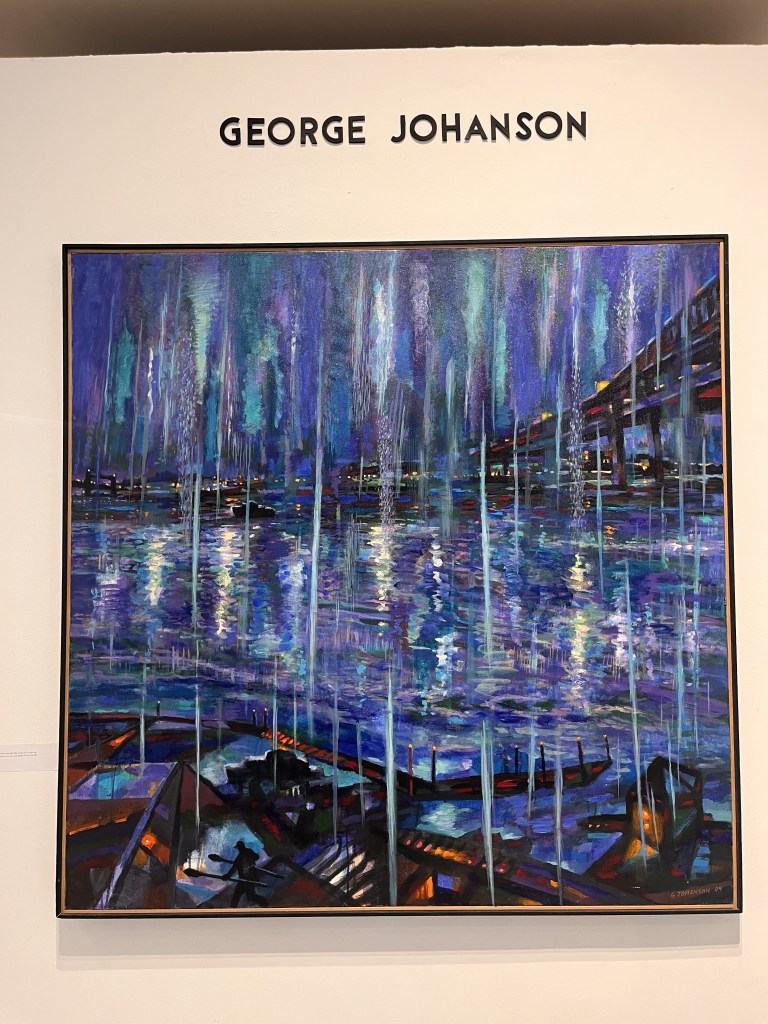

In the rain series, Johanson found a calling with vertical lines to further contort viewers’ perception of pictorial space. It both unifies and mystifies an image with that additional texture. And the rain is at the center stage of the painting titled Rain and River V. In fact, it was probably pouring. Rainwater lightens up the zigzag passageway near the bottom, capturing here and there warm artificial light against the blue patches. The Marquam Bridge pierces through diagonally on the top. In between sits the Willamette River shivering with reflection. A mysterious figure carries oars in the downpour. Johanson was not frugal in rendering the rain. The paint was dripped and dragged down forcefully but deliberately. It’s meant to be felt as if we are drenched so much that our vision becomes obscured.

In the middle of August, that feels great.

Leave a comment